A free press is an essential ingredient for a free society. Speaking the truth to power and holding authorities to account means the general public does not fall victim to endless streams of fake news and propaganda.

Journalists often act as intermediaries between citizens and those in power, attempting to achieve transparency and providing insight for both sides.

Kind of like a marriage counselor. But one that airs everything out in the national media.

One side of their role is to report on what the authorities are up to. This keeps the wider population informed and able to make educated political decisions.

The other side is reporting on the social issues that affect people in their daily lives. This gives the state a better understanding of how their policies are impacting different groups.

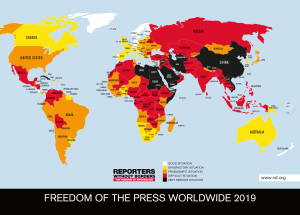

Worryingly, though, only 9% of people around the world live in a country where press freedom is “good,” as determined by Reporters Without Borders.

And in many places, things are getting worse. Not better.

With that in mind, we thought it would be a good time to reflect on freedom of the press. How do different countries uphold or threaten its virtues? And what challenges do journalists and their sources face?

Here’s a look at the state of press freedom in a few countries that could be doing far more to protect this important part of society.

What makes it possible for a totalitarian or any other dictatorship to rule is that people are not informed; how can you have an opinion if you are not informed? If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.Hannah Arendt

Brief history of press freedom in the U.S.

No government ought to be without censors; and where the press is free, no one ever will.Thomas Jefferson

Indictments under the Espionage Act of 1917

You may be surprised to hear that before the Obama administration in 2008, there were only three known cases where the Espionage Act was used to indict government officials relating to leaks:

- Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo – Responsible for leaking the photocopied documents that make up the Pentagon Papers, which the New York Times published in 1971.

- Samuel Morison – The only American government official ever convicted for giving classified information to the press, Morison is a former intelligence professional convicted in 1985 for delivering classified images to magazines run by Jane’s Information Group.

- Lawrence Franklin – A former U.S. Department of Defense employee, Franklin passed classified documents relating to America’s policy towards Iran to Steven Rosen and Keith Weissman, both members of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee.

The Obama administration added six cases to the list.

Yes, you read that correctly. The number tripled under a single President.

1. Thomas Drake, April 2010

National Security Agency official Thomas Drake was indicted for communicating with a Baltimore Sun reporter about the NSA’s Trailblazer project, a domestic surveillance program. In 2011, Drake pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor unrelated to the Espionage Act and avoided a 35-year prison sentence. Drake was instead sentenced to probation and community service.

2. Shamai Leibowitz, May 2010

FBI translator Shamai Leibowitz pleaded guilty to sharing classified information about FBI wiretaps with a blogger and was sentenced to 20 months in prison.

3. Chelsea Manning, June 2010

Army private Chelsea Manning was arrested for allegedly leaking 250,000 classified documents to whistleblower website WikiLeaks and was indicted under the act in 2012. Manning pleaded guilty to lesser charges but entered not guilty pleas to charges under the Espionage Act. Her case is ongoing, and as recently as March 2019 she was jailed for refusing to testify before a grand jury against Wikileaks and its leader, Julian Assange.

4. Stephen Kim, August 2010

Stephen Kim, a State Department contractor, was indicted for giving classified information about North Korea to Fox News. And in 2014 he was given a 13-month prison sentence.

5. Jeffrey Sterling, December 2010

Former CIA officer Jeffrey Sterling was indicted for talking to a New York Times reporter about a CIA program targeting Iran’s nuclear program in the 1990s and was arrested in January 2011. The Times reporter, James Risen, was subpoenaed to testify in Sterling’s trial. It took a seven-year legal fight from Risen to protect his confidential sources, despite the Obama administration taking rare steps to renew the subpoena. Sterling, for his part, received a 42-month prison sentence. He was released in January 2018 after serving more than two years.

6. John Kiriakou, January 2012

John Kiriakou, another ex-CIA officer, was indicted for giving a reporter the name of an undercover agent and speaking to ABC News about the CIA’s practice of waterboarding interrogations. Despite the Justice Department concluding that Kiriakou had committed no crime in 2007, the case was reopened under the Obama administration and Kiriakou was charged. He served 23 months in prison.

And that list doesn’t even count the contractors, including Edward Snowden, that were also subjects of criminal prosecutions under the 1917 Espionage Act during Obama’s time in office. All accused of leaking classified information to the press.

Reporters’ phone logs and emails were seized without notice, despite no reason being given. And, thanks to the classified documents released by Snowden, we know that extensive surveillance by the NSA takes place even when it comes to regular citizens.

How does all this affect journalists and the free press?

Well, the knowledge of criminal investigations and government surveillance means that sources become much more reluctant to disclose information. It also makes it very difficult for a journalist to protect their sources when they do come forward.

Under George Bush, expressions of anger were voiced at various stories, including the revelations on torture at Abu Ghraib and warrantless wiretapping. However, journalists and news executives were still able to engage in productive dialogue with government officials, according to a report by former Washington Post editor Leonard Downie Jr.

Things changed for the worse with Obama in charge.

Promises of transparency completely failed to materialize as the 44th President oversaw record high numbers for the percentage of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests answered with redacted files or nothing at all.

As Margaret Sullivan, public editor of the New York Times, wrote back in 2013, “Instead, it’s turning out to be the administration of unprecedented secrecy and of unprecedented attacks on a free press.”

During the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, Barack Obama gave speeches that took aim at the press and its coverage of Donald Trump’s campaign.

The job of a political reporter is more than just handing someone a microphone. It’s to probe and to question and to dig deeper.

He continued:

Good reporters find yourselves caught between competing forces, I’m aware of that. You believe in the importance of a well-informed electorate. You’ve staked your careers on it. Our democracy needs you more than ever.

Riiiiight. Good talk, Barry.

But it sure seems like you tried pretty hard to stop journalists from being able to probe and question and dig deeper. Even when it comes to health-related stories that would clearly be in the public interest to report.

Have things improved under Donald Trump?

TL,DR: nope.

Freedom of press may actually be in a worse state than ever before.

On his first full day in office as commander-in-chief, Donald Trump called journalists “the most dishonest human beings on earth” due to what he claimed to be false reports on the size of his inauguration crowd.

You know what they say, start as you mean to go on.

The very next day, the new President labelled the U.S. news media as an “enemy of the American people.”

Hardly the kind of language that seems supportive of a free and open press.

It’s not exactly surprising, then, to find that the number of leak investigations has tripled again compared to the end of the Obama era.

And just like his predecessor, Trump is also using the Espionage Act to prosecute those who are suspected of publicly disclosing classified information.

1. Reality Winner, June 2017

One prominent example is from June 2017, when the Department of Justice filed a criminal complaint under the Espionage Act against Reality Winner. The contractor was suspected of leaking an NSA document to The Intercept regarding Russian interference in the 2016 election.

An odd detail in Winner’s case is that she was denied bail on the grounds of being dangerous to society. Meanwhile, Paul Manafort was able to avoid jail by posting $10 million, and was even able to enjoy a Christmas getaway.

Manafort was convicted for aiding the Russian effort. Winner’s crime, on the other hand, was simply warning Americans about it.

Eventually, a plea deal was reached, and Winner was handed a five-year prison sentence.

2. Terry J. Albury, March 2018

Another case shows that the FBI is now using FOIA requests, made by the media, to identify sources.

Terry J. Albury, charged in March 2018 under the Espionage Act, leaked information relating to national defense to a journalist.

In the affidavit for his arrest, it’s described how the dates of two FOIA requests were used to identify Albury as the key suspect for the leak.

Oh, and the seizure of phone and email records? Yes, that still happens.

As part of an investigation into a former Senate Intelligence Committee aide, James Wolfe, the FBI secretly seized records from New York Times reporter Ali Watkins.

Despite claims that they were only looking for one of her sources, what they took was a volume of phone calls and emails stretching back multiple years.

Only a tiny bit suspicious.

As Suzanne Nossel, chief executive officer of PEN America, said in PEN America’s official statement about this practice:

The fact that the FBI seized a journalist’s personal and professional phone and email records, going back years, will cast an inevitable chill on newsgathering at a time when the role of the press in holding government accountable is critically important. This is particularly the case given that the alleged leaks in question relate to allegations of inappropriate and potentially unlawful conduct on the part of a major presidential political campaign.

Freedom of press around the world

United Kingdom

The UK rose up the ranks by seven places in the World Press Freedom Index, published annually by Reporters Without Borders.

However, Britain continues to be one of the worst-performing countries in Western Europe, and a number of major concerns are still in play.

Particularly when it comes to national security, surveillance, and data protection.

A 2018 report by Privacy International found that UK police can download all the data from your phone, without permission or a warrant.

What does this include?

From contacts and call logs to emails and messages (even deleted ones!), the police can grab it all by connecting smartphones to extraction devices. The information is then used to generate a report that can pinpoint your location at different times and provide details of conversations you’ve had.

Third-party apps also get affected by this technique, including some you may think are safe like WhatsApp.

That’s not all. Since it’s apparently not possible to isolate a certain type of data, it means texts and photos not relevant to investigations are also extracted.

A recent high-profile story illustrates how even the victims of crime in the UK are being asked to hand over their data, or their case may not even be investigated.

Sounds great.

Now consider being a journalist trying to protect their sources. The complications become apparent very quickly.

Just like their American counterparts across the pond, journalists are finding it more and more difficult to present information given to them. Particularly if it involves leaking confidential documents to the general public.

No stone unturned

Two men who found this out the hard way are Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey.

These journalists from Northern Ireland had their homes and offices raided by police in the summer of 2018.

Officers were looking to find evidence against the journalists, who were both arrested on suspicion of stealing confidential information included in a documentary about the 1994 Loughinisland massacre.

With the title of the documentary in question being No Stone Unturned, the irony of the raids is certainly hard to miss.

Items seized during the searches include various documents and computer equipment, but Birney and McCaffrey claim the information was given to them by an anonymous source.

More recently, the men were told that their bail would only be extended if they agreed not to talk about aspects of the case. A move that both Amnesty International and the National Union of Journalists spoke out against, due to the risk it poses to press freedom.

And of course, Wikileaks founder Julian Assange currently finds himself inside a British prison after police officers were invited into the Ecuadorian embassy, where he had previously been granted asylum.

Serving a 50-week sentence for breaching bail conditions in the UK is likely to be the least of Assange’s concerns, though. There’s also a chance that the British government could extradite him to the U.S., where he would face more serious charges relating to his work with Wikileaks.

Turkey

Since a failed coup attempt by the Gülen movement in 2016, the Turkish government has opted for an all-out assault on press freedom.

You could try and give them the benefit of the doubt and say, “Sure, when a terrorist organization tries to overthrow those in power, a temporary crackdown could be a legitimate move.”

But three years later, with journalists still being arrested and no end in sight, it’s clear now that the move is far from excusable.

Especially since not only those affiliated with Gülenist media groups are being targeted.

Secular, Kurdish, leftist, and many other journalists that dare to challenge official narratives are all falling victim to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s heavy-handed approach.

Government officials say that the 139 journalists currently imprisoned in Turkey are there because of criminal activity, rather than their work as reporters.

Right, we totally believe that.

Two cases stand out in showing just how bizarre the crackdown has become.

Zehra Doğan

The first saw Kurdish journalist and artist, Zehra Doğan, serve nearly three years in prison.

Her crime?

She created a watercolor based on a photograph of actual events.

Depicting the city of Nusaybin destroyed by Turkish military forces was enough to convince authorities that Doğan must be linked to a terrorist organization. Namely, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Many activists and journalists rallied around the case.

Banksy, the world famous street artist, even unveiled a mural to protest her arrest.

Think that’s bad?

Well, things are about to get super weird.

Musa Kart

Imagine being a cartoonist for a daily newspaper.

Now imagine that newspaper helps to expose the Gülen terrorist organization that wants to overthrow the government.

All good, right? Mr. Erdoğan probably has some kind of reward in mind for the staff, including you.

How about being arrested for helping the terrorist group instead?

Wait. What!?

That’s the precise experience Musa Kart went through, along with 16 colleagues from the editorial staff of Cumhuriyet, one of Turkey’s oldest newspapers.

Kart was sentenced to 3 years and 9 months in prison for “aiding and abetting terror groups without being a member,” with an appeals court recently upholding the decision.

Egypt

Egypt has long been an enemy of press freedom. And its 2019 ranking of 163 out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index highlights that.

Journalists and media outlets in the country have encountered a wide range of issues for many years.

These include being pressured out of work for criticizing the government, getting attacked by police while covering protests, and facing fines or detainment for reporting on sensitive issues.

And that’s all before we get to the worst of it.

On 14 August 2013, Egyptian security forces stormed two demonstrations in Cairo. One was taking place at al-Nahda Square, and the other at Rabaa Adawiya Square.

Police in riot gear opened fire on protesters in attendance with tear gas and birdshot.

A supporting cast of bulldozers and armored vehicles were also deployed to help clear barricades, and a group of rooftop snipers fired upon those attempting to escape.

Human Rights Watch reported that around 1,000 people lost their lives during the massacre, which the organization labelled a “crime against humanity.”

Among the victims were four journalists covering the events for various news media outlets:

- Ahmed Abdel Gawad, a reporter for the state-run Al-Akhbar newspaper, was shot dead.

- Habiba Ahmed Abd Elaziz was also shot while reporting for the local Dubai newspaper XPRESS.

- Mosaab al-Shami, a photographer for the local Rassd News Network, was trying to flee gunfire when a sniper shot him in the chest.

- Sky News cameraman Mick Deane was killed by gunshot while working at the scenes with Sky’s Middle East correspondent, Sam Kiley.

Today, freedom of the press is still under threat in Egypt.

The government routinely seeks to punish critical voices. In some cases, confiscating entire newspaper runs that point out failures of the administration. And in others, trying to kick foreign news media offices out of the country.

Australia

Much like the U.S. in the fallout of the September 11 attacks in 2001, Australia has recently passed a series of new laws under the guise of national security.

But some see the changes in a different light.

The decisions may have been made with good intentions, but they could easily result in media intimidation, helping in the hunt of whistleblowers, and the locking down of information.

In December 2018, the government passed controversial laws that enables police and other agencies to extract information from encrypted systems.

Authorities are now able to force companies like WhatsApp to create back doors that would give them access to encrypted messages without the user knowing about it.

As the Sydney Morning Herald points out, this is not good news for journalists.

Definitely a SMH moment. Only me who gets that? OK never mind.

Tech firms who don’t comply with the laws will be fined.

That’s because identifying a whistleblower or the source of a news story becomes incredibly easy. If not by gaining access to the messages themselves, then by using associated metadata.

Sometimes, this is more revealing than the exchanges with the source.

How?

Well that’s down to metadata disclosing the journalist’s relevant location history.

Two other laws rushed through the Australian Senate are even more alarming.

Passed in June 2018, the Espionage and Foreign Interference Bill introduced new offences relating to spying, sabotage, and the theft of secrets on behalf of a foreign government.

And the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Bill means that those acting on behalf of foreign agencies are now placed on a register.

The changes include prison sentences of up to 20 years for publishing protected information.

So, basically making it illegal for a journalist to do their job when a whistleblower comes forward.

Great move, Australia.

Reporters Without Borders described the new laws as “Draconian,” with Australia falling to 21st place in the World Press Freedom Index.

Conclusion

Freedom of the press, if it means anything at all, means the freedom to criticize and oppose.George Orwell

Authoritarian governments have a number of tools at their disposal when it comes to maintaining order and controlling the narrative.

They can restrict access to social media sites and block news outlets they deem unfit.

Banning VPNs is another favorite play straight out of How to Be A Dictator for Dummies.

And of course, surveillance systems are likely keeping an eye on citizens while they’re offline too.

That’s why a free press remains extremely important in all countries around the world. It helps to keep authorities in check by revealing their most heinous decisions and actions.

For that reason, we continue to offer CyberGhost VPN free of charge to journalists, NGO representatives, and other organizations that actively fight for a free and secure internet. It’s all part of our ongoing digital freedom program.

Please share our digital freedom program with anyone you think may need it.

Leave a comment